Posted by MK Research on Jan 8th 2023

History of the Dallas Airplane Ceiling Fans

On May 22, 1919, Raymond Orteig of New York City offered a prize of $25,000 "to be awarded to the first aviator who shall cross the Atlantic in a land or water aircraft (heavier-than-air) from Paris or the shores of France to New York, or from New York to Paris or the shores of France, without stop."

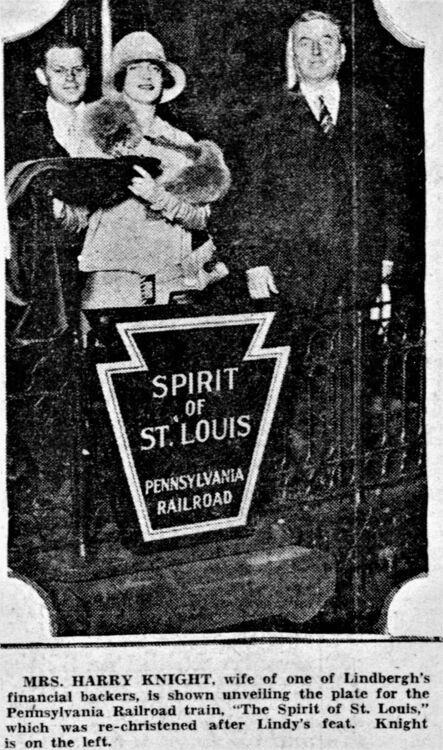

Besides Lindbergh, there were four serious contenders for the Orteig prize, one of which was Commander Richard Byrd, the first man to reach the South Pole. Lindbergh's courage and enthusiasm for such a flight were not enough; he needed financial backing. Lindbergh found his financial answer in Harry H. Knight, a young aviator who could usually be found bumming around the Lambert Field in St. Louis. This was the beginning of the Knight-Lindbergh partnership that would soon change the course of aviation history.

After being denied any financial assistance by several of St. Louis's businessmen, Lindbergh made an appointment with Knight at his brokerage office. Knight, the president of the St. Louis Air Club, was fascinated with Lindbergh's plan and called his friend, Harold M. Bixby, president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce. Bixby also displayed a strong interest in the obscure stunt flyer and mail pilot. Together Knight and Bixby formed an organization called "the Spirit of St. Louis", which was dedicated to gathering funds for the flight. More than $10,000 was needed in order to build a single engine plane and acquire the proper equipment.

Knight went to his father, Harry F. Knight, who was a major power in the realm of finance and an equal partner in the firm Dysart, Gamble & Knight Brokerage Company. Like his son, the senior Knight was interested in the aviation field and backed every effort to make America conscious of airplane transportation. In December 1926, Lindbergh presented his plan to stockbroker Harry H. Knight, another of his contacts from Lambert Field and president of the St. Louis Flying Club. Knight was rather enthusiastic and told Lindbergh to concentrate on organizing the flight rather than raising the estimated $15,000 needed to fund it. Knight then called banker Harold Bixby, who set up a meeting for the following week.

Bixby and Knight told Lindbergh that the plan was feasible—if he could keep the costs within his estimate. They also enlisted Knight’s father, Harry F. Knight; Bill Robertson’s brother, Frank; Albert Bond Lambert’s brother, J. D. Wooster Lambert; and E. Lansing Ray, publisher of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat newspaper, and borrowed $10,500 to add to the amounts already committed by Lindbergh, Thompson, Lambert, and Robertson.

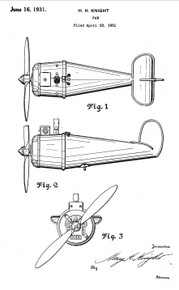

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh makes the record breaking flight to Paris, flying non-stop across the Atlantic ocean from New York, landing in Paris, France, and is hailed freely as an international hero. The world is overcome with admiration for Lindbergh, aviation and everything American. Thereafter, speculators and business men start marketing Lindbergh and aviation-themed products, such as fans shaped like aircraft to cash in on the hot demand for such products. Harry H. Knight, along with his father, Harry F. Knight's connections and financial backing, begin marketing and the Knight's start to jump on the Lindbergh Trans-Atlantic Flight marketing bandwagon. Dallas Engineering Co., Dallas, Texas, an aviation fabrication shop, is contracted by the Knights to build the fans for market as early as 1929, having filed for the United States trademark registration of "Dallas Airplane Fan" and receiving a design patent for the airplane fan production design in 1931. The initial production fans are observed to use Century Electric motors, and were a marketing sensation.The "Dallas Airplane" fans consisted of a wingless airplane fuselage, having cast-aluminum two wing blade blades. A scent diffusing receptacle was set in a box atop the earlier fans, taking advantage of motor heat to release a pleasant fragrance along with the breeze provided by the fan. Finishes for the fuselage consisted of copper washed or "Terne", a form of tin-plating. There were three models of airplane fan for sale to prospective buyers: The Model 119 had a single-speed 1750 rpm motor and a 19-inch blade. The Model 122 had a 1750 single speed motor, but with a larger 22-inch blade. Lastly, the Model 123 had the same 22-inch blade as the Model 122, with the addition of a two speed 1200 and 1800 rpm motor.

Around 1935, there were revisions to the design of the Dallas Airplane fans, primarily the discontinuation of using Century Electric motors and phasing in General Electric 1/6th horse power, 1750 rpm motors, and the omission of the scent diffuser previously added to the top of the motor housing. The front motor was changed slightly to accommodate the new GE motors. By 1936, there were further changes in production design, lasting until approximately 1939. The Model 122 and 123 were still available, as in past years, however, the new Model 419, having a 19-inch blade and a two-speed motor and the new Model 422, having a 22-inch blade and a two-speed motor were introduced. These fans have a bullet shaped rear motor cover, and were available at extra cost with a conventional down-pole ceiling mount, an ornate cast wall mount, an early cast-iron pedestal base having a clamp-adjusted and "question-mark" shaped motor suspender, as well as the "Modernistic" pedestal mount, which had a cast-iron base, telescopic height adjustment, and a cast support ring which the motor was suspended by. Octagonal protective cages were also an option as of this date, regardless of style or model. Dallas Airplane Fan also produced a three-wing exhaust fan. Other more conventional circulators were also sold the same years as the Dallas Airplane Fans were sold and manufactured by Dallas Engineering Co., the "Knight Cyclone", a single-speed, ceiling suspended 1750 rpm Century motor having cast-aluminum two-winged blades, and a similar construction fan marketed as the "Knight-Gibson Whirlwind", having the 1750 rpm Century Electric motor and similar cast two-winged blade, available as a ceiling down-pole suspended circulator assembly, as well as a cast-iron pedestal base, having a non-adjustable "question-mark" shaped motor suspension.

1939 seems to be the last year Dallas Airplane fans were sold, mostly old stock, and were very profitable for the company, being sold at least ten to one in comparison to rival circulator manufacturers. The Dallas Airplane Fan in any configuration is a historically significant, functional and stylish addition to anyone fortunate enough to own one. Quality examples are certain to increase in value, eagerly sought by the antique fan collecting community

.thumb.jpg.0b62a35e3f7a34844bc096ce0921bbc4.jpg)